BASIL ALKAZZI-

THE RITES OF SPRING...

BY DONALD KUSPIT

The romantic tradition of the abstract sublime– of visionary space imbued with spiritual import– has been with us at least since Turner, and it is William Turner' s light that informs Basil Alkazzi's visionary images of nature. The Rites of Spring form one group and Ascension and Eternal Whisperings taken together, form another group. Each engages nature in a different way; they represent the extremes of communion with nature. The Rites of Spring convey ecstatic immersion in nature; Ascension and Eternal Whisperings suggest a certain detached admiration of it. In the former, light is eternal– immanent in matter, and transforming it so that it seems immaterial. In the latter, light is external– explicitly from the beyond. The flowers of The Rites of Spring are blossoms of light; the circular heavenly objects– some are like comets, others suggest astral bodies– in Ascension and Eternal Whisperings bring the gift of light to the earth, coming from a great distance to illuminate our meagre world. The flowers are dynamic life-force auras– sheer rhapsodic radiance. In contrast, the heavenly objects are more self contained, whatever their auric flair. The light of both is uncanny and eerie, but the luminosity of the earthbound flowers is yellow and incandescent, while the gemlike heavenly objects shine with a brilliant white light, appropriate to their remote, cosmic character. Basil Alkazzi's flowers and objects look delicate, but their buoyant, incessant light gives them a cosmic vigour and intensity, giving his pictures as a whole an inner grandeur and sweep that belies their modest dimensions.

But these paintings are not only about Basil Alkazzi's attitude to nature, but about nature itself. Nature is once again miraculous, unsoiled, sacred in them. It is an embodiment of divine creativity, making it manifest even as it conveys its enigma. It is Basil Alkazzi's Transcendentalism that is so remarkable, all the more so in this profane age. The impressive thing about his images is their Emersonian idealism, or, as the phenomenological theologian Robert Corrington elegantly calls it, their "ecstatic naturalism." "While we cannot return to a romanticized or eulogistic understanding of nature," Corrington writes, "it is possible to realign the human process with those natural and spiritual potencies that give shape to meaning and communication. Ecstatic naturalism is a perspective that honours the self transcending potencies within nature which continually renew the order of the world."1

Basil Alkazzi's rapturous life-force flowers are like burning bushes that signal the presence of the divine, and his heavenly objects invade and overpower human space, making it into something more magical– unfathomable– until we can no longer discriminate between human and cosmic space– literally take leave of our senses. If Ascension VIII shows heavenly light forcefully invading the atmospheric blue sky of the earth, then Ascension VI and Ascension VII convey the ultimate mystical state: merger with the divine light has eliminated all traces of earthly presence. The light in the former is thin and elusive, the light in the latter is dense and impacted. But in both it suffuses the surface. Both works convey the moment of gnostic illumination, when the forces of darkness– they are subliminal even in the seemingly pure blue of the sky– are overcome and the material world is completely destroyed. [That sky blue is associated with the earth for Basil Alkazzi is evident from Eternal Whisperings I, V, and VI where bright green foliage appears. In Eternal Whisperings in Spring III, IV, and V the sky becomes yellow, completely luminous, suggesting a dematerialization and spiritual transformation process. This seems to be confirmed by the fact that the foliage slowly but surely loses its green, finally becomes as radiant as the sky. In general, for Basil Alkazzi the process of spiritualization involves the release– in effect recovery– of the light that is the energy source for the process of photosynthesis by which green plants produce carbohydrates from carbon dioxide and water. It is the basic process of organic creativity, and carbohydrates contain only carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, the basic elements of life.]

But that is not the end of the spiritual story: consummately all over, the light spawns–- with a kind of parthogenetic fury [the absolute can create lone, indicating what Corrington calls its self-transcending potency]-- heavenly bodies. They are a form of spiritual– as distinct from natural– life: they are "supernaturally" pure life. Sometimes they shoot rays that explosively skim across space, at other times they generate an auratic atmosphere that surrounds them like a protective membrane. In all cases achieving a state of mystical dedifferentiation, in which earthly self and divine light fuse– or rather in which the former dissolves or melts in the latter– leads to a new cosmic differentiation, that is, a mystical new beginning of life. Basil Alkazzi's heavenly circles are like spores waiting for he right artistic moment to release their power of life.

The literally marvellous and wondrous life-force flowers of The Rites of Spring– they convey the fascination nature has for the artist– combine the traditions of European and American mystical nature imagery. They have a family resemblance to Mondrian's flower paintings, which have come to be regarded as a crucial part of his oeuvre, and which he continued to make throughout his career, as though suggesting that nature had as much spiritual import as the geometry his abstractions celebrated. Eternal geometry has been familiar since Plato, but eternal nature was familiar long before him, as the writings of the Pre-Socratics indicate. The art historian Hugh Honour has spoken of "the morality of the landscape" when describing nineteenth century romantic painting2, but underneath this morality, and more crucial and emotionally influential than it– indeed, the expressive core that makes nineteenth century landscape painting truly romantic– is what must be called the mysticism of landscape.

I have already described the mystical dimension of Basil Alkazzi's images, but I want to emphasise that the flowers in The Rites of Spring can be understood– however strange it may seem to do so– as enlarged abstract versions or abstract close-ups of the wild flowers in Constable's Dedham Vale [1828], just as Basil Alkazzi's Eternal Whisperings can be derived from Constable's cloud studies, particularly those in which light majestically breaks through the clouds. Similarly, Basil Alkazzi's light has the same inner munificence as William Turners' light. However much Basil Alkazzi presents his light in a more ritualistic way. But then Turner's light has a recurrent pattern– an inner rhythm or abstract current.

The Rites of Spring also fit into the American landscape tradition, both by way of the complexity of their light– like the Luminists, Basil Alkazzi is able to convey the nuances of ever changing light without finitizing it– and their rendering of organic growth. His nature more than holds its own and conveys the mystery and excitement of organic life in abstract terms. They convey a distinctly American sense of nature as a living, in-containable force and process, the ultimate source of creativity, transcending its own organic creations. The Rites of Spring is of course the title of Stravinsky's composition, but Basil Alkazzi's pictorial version convey an American sense of untamed and untameable nature, not simply raw nature– of nature altogether beyond the reach of the exploitive civilization, not simply preceding it. Primitivism at its most pure and authentic involves an idealization of nature at the expense of humanity– which is always corrupting rather than appreciative– and it is this spiritual primitivism that we find in Basil Alkazzi's mystical nature imagery as well as in the American transcendentalist primitive painters. In both their work and Basil Alkazzi's there is a sense of natural paradise found rather than lost, indeed, of a prelapsarian paradise of emotional experience

Basil Alkazzi has found the vital achetype of cosmic nature within that of mundane nature. He shows that what seems to be a hollow form has an archetypal content. His rich colour and dynamic line go a long way towards convincing us that his life-force flowers and heavenly objects have archetypal import– towards re-originating them as spiritual entities, indicating that natural life is simultaneously spiritual life, and as such a sign of the spiritual purpose and sacred character of the cosmos. His life-force flowers blot out the horizon or boundary between heaven and earth, and he shows us heavenly objects about to burst through it, suggesting that the seperation of natural space and cosmic space– implicitly matter and spirit– is far from absolute. It is only in this regard that he disagrees with Emerson, who declared that "the health of the eye seems to demand a horizon"3. Basil Alkazzi shows us that the eye is really healthy when it can see beyond the horizon, without any frame for its consciousness.

Basil Alkazzi “Ascension VII”

Gouache on Handmade paper, 57 × 75 cm. 1999

Basil Alkazzi “Ascension VIII”

Gouache on Handmade paper, 35 × 45 cm. 1999

Basil Alkazzi “The Rites of Spring II”

Gouache on Handmade paper, 30 × 44 cm. 1999

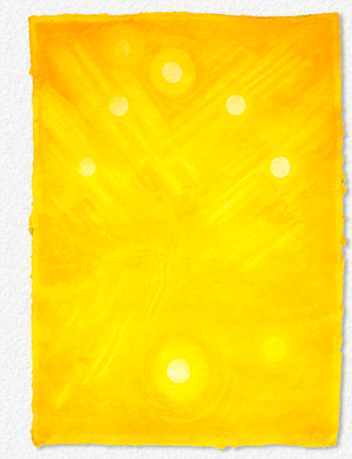

Basil Alkazzi “The Rites of Spring II”

Gouache on Handmade paper, 30 × 40 cm. 1999

Basil Alkazzi “The Rites of Spring V”

Gouache on Handmade paper, 32 × 44 cm. 1999

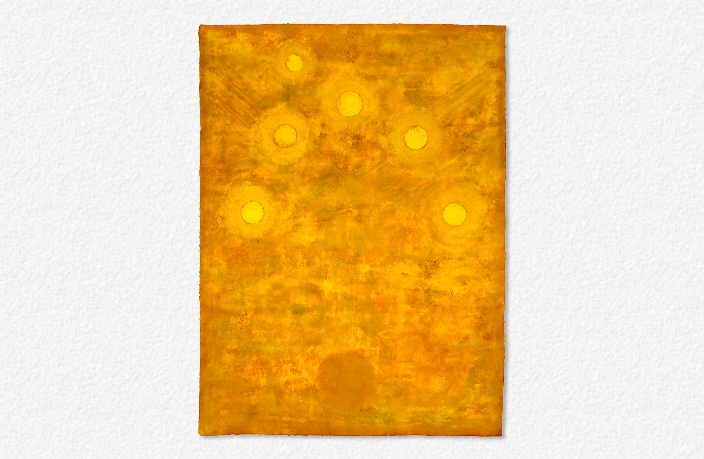

Basil Alkazzi “The Rites of Spring IV”

Gouache on Handmade paper, 30 × 44 cm. 1999

Basil Alkazzi “The Rites of Spring III”

Gouache on Handmade paper, 30 × 44 cm. 1999

Basil Alkazzi “The Rites of Spring VIII”

Gouache on Handmade paper, 57 × 76 cm. 1999

Basil Alkazzi “The Rites of Spring IX”

Gouache on Handmade paper, 30 × 40 cm. 1999

Basil Alkazzi “The Rites of Spring VI”

Gouache on Handmade paper, 30 × 40 cm. 1999

Basil Alkazzi “The Rites of Spring XIII”

Gouache on Handmade paper, 57 × 76 cm. 1999

Basil Alkazzi “The Rites of Spring XIV”

Gouache on Handmade paper, 57 × 76 cm. 1999

Basil Alkazzi “The Rites of Spring XI”

Gouache on Handmade paper, 30 × 40 cm. 1999

Basil Alkazzi “Eternal Whisperings III”

Gouache on Handmade paper, 57 × 76 cm. 1999

Basil Alkazzi “Eternal Whisperings IV”

Gouache on Handmade paper, 57 × 76 cm. 1999

Basil Alkazzi “Eternal Whisperings VI ”

Gouache on Handmade paper, 57 × 76 cm. 1999

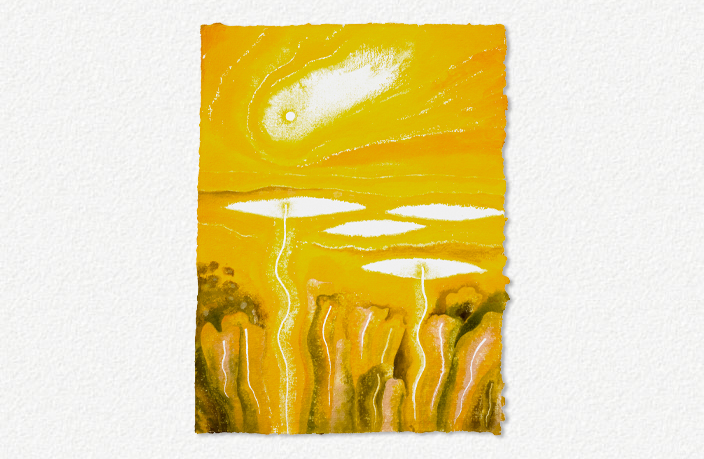

Basil Alkazzi “Eternal Whisperings in Spring III”

Gouache on Handmade paper, 57 × 76 cm. 1999

Basil Alkazzi “Eternal Whispherings in Spring IV”

Gouache on Handmade paper, 57 × 76 cm. 1999

Basil Alkazzi “Eternal Whisperings in Spring V”

Gouache on Handmade paper, 57 × 76 cm. 1999

Basil Alkazzi “The Rites of Spring XVI”

Gouache on Handmade paper, 35 × 52 cm. 2000

Basil Alkazzi “The Rites of Spring XV”

Gouache on Handmade paper, 30 × 39 cm. 2000

Basil Alkazzi “The Rites of Spring XVII”

Gouache on Handmade paper, 57 × 76 cm. 2000

Basil Alkazzi “The Rites of Spring XVIII”

Gouache on Handmade paper, 57 × 76 cm. 2000

Notes:

1. Robert S. Corrington, Nature and Spirit (New York Fordham University Press 1992) p.x.

2. Hugh Honour, Romanticism (New York Harper & Row 1979) p.57

3. Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nature Addresses, and Lectures (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press 1979) p.13.

Full text copyright 1998 by Donald Kuspit and K.IZUMI Art Publications Ltd.

Full text copyright 1998 by Basil Alkazzi and K.IZUMI Art Publications Ltd.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American copyright conventions.