SELECTED COLLAGE

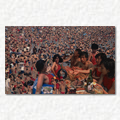

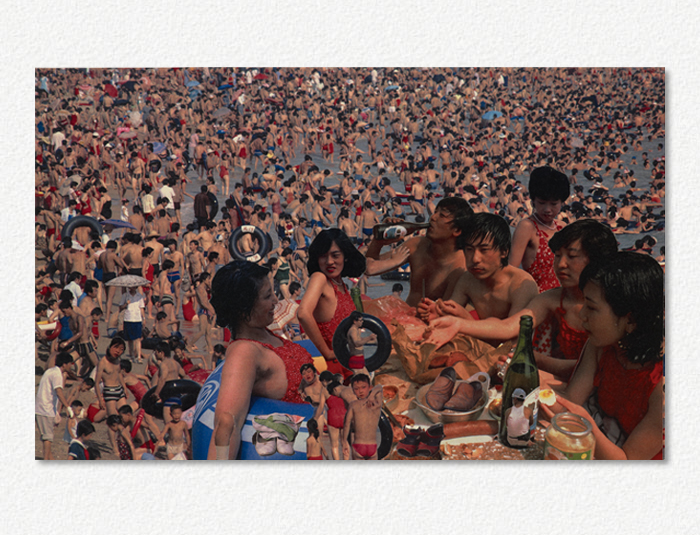

.... I've mentioned that I think Alkazzi's collages and photomontages have special significance in his oeuvre. They're consummately beautiful; different elements harmonize in a garden of paradise, sometimes mountainous, sometimes a hortus conclusus, always serenely vital. For all the activity and crowds of people in At the Beach, a memory of Alkazzi's visit to Japan, the figures are happily together, whether seen up close at the banquet table in the foreground or in the crowd in the distant background. Wherever they are, they are all very particular individuals, all young, all enjoying life.

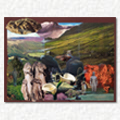

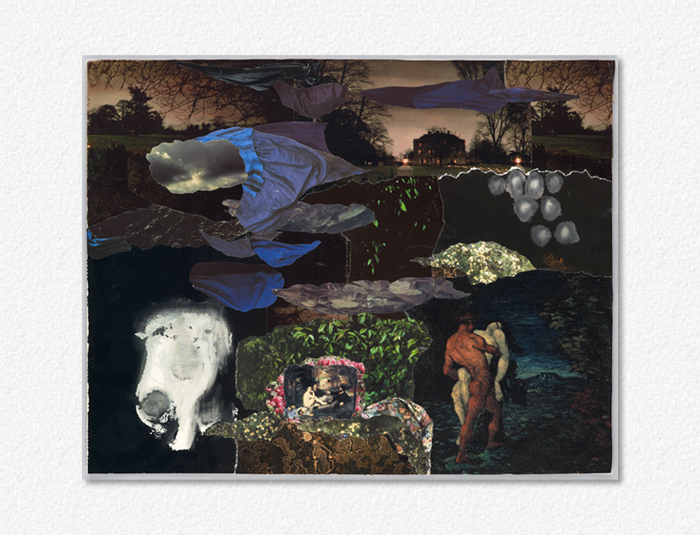

Even when, as in The Rape, the picture fragments into physically incompatible parts, reminding us that "there is no excellent beauty that hath not some strangeness in the proportions," as Francis Bacon wrote, 8 it remains self-consistent emotionally. The parts are all actors in the same violent drama. But what makes The Rape, and all the other collages and photomontages particularly interesting, is their quotation—postmodernists would say appropriation—of historically important works of art. Some are modern, like Manet's Oejeuner sur l'herbe, 1863, which alludes to Giorgione's traditional Pastoral Symphony, ca. 1508, and is the centerpiece of The Rape. Two of the heads, one of a naked female, the other of a clothed male, from the Manet make a brief appearance in Landscape of Dreams V, another collage.

Even when, as in The Rape, the picture fragments into physically incompatible parts, reminding us that "there is no excellent beauty that hath not some strangeness in the proportions," as Francis Bacon wrote, 8 it remains self-consistent emotionally. The parts are all actors in the same violent drama. But what makes The Rape, and all the other collages and photomontages particularly interesting, is their quotation—postmodernists would say appropriation—of historically important works of art. Some are modern, like Manet's Oejeuner sur l'herbe, 1863, which alludes to Giorgione's traditional Pastoral Symphony, ca. 1508, and is the centerpiece of The Rape. Two of the heads, one of a naked female, the other of a clothed male, from the Manet make a brief appearance in Landscape of Dreams V, another collage.

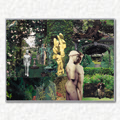

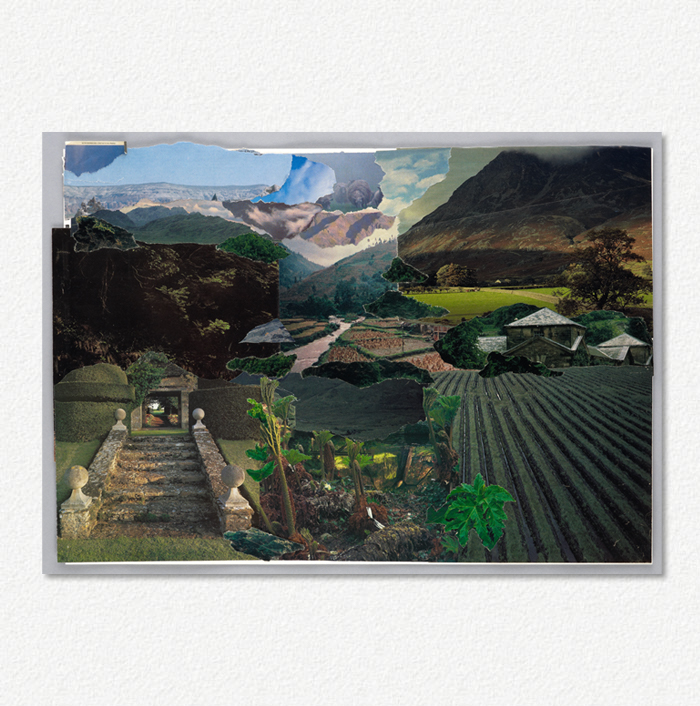

Other appropriations are ancient, like the archaic sculptures of Apollo and

of Kleobis and Biton, two standing male youths (kouroi), in a garden of paradise,

inventively pictured in a 1995 collage. They stand in the foreground, the Apollo in

the middle ground, and in the background three other naked male figures stand

together, the two made of bronze shown back and front, one made of stone like the

Apollo, Kleobis, and Biton figures, all more mature and classical in style than they.

It is as though we are looking at three male Graces rather than three female Graces.

The fragments of a sculpture of a male figure stand in the center of the work. It

is as though they have been recently excavated from the past, and are waiting to

be put together in a glorious whole, like the other figures. But the disconcerting

fragmentation of the figure suggests it may be a discombobulated modern sculpture.

It's springtime in the garden—the flowers, many pure white, are in full bloom, and

the foliage is radiantly green. All the figures are handsome and statuesque, majestic

and sacred, in the prime of life, their bodies perfect and healthy—whole and

wholesome, unlike the absurd "modern" sculpture. They are presided over by what

seems like a mother goddess, a few strands of luminous gold draping her naked

brown torso and one arm. In other pictures the feminine makes its presence felt in

the colorful petals that hover in the air, levitating like spirits. In still other pictures

a rather grand—enormous—female head presides over the scene. In yet others two

female figures, solid classical goddesses or ghostly Elizabethean ladies, watch over

the male figures, caring for them as Mother Nature does.

Other appropriations are ancient, like the archaic sculptures of Apollo and

of Kleobis and Biton, two standing male youths (kouroi), in a garden of paradise,

inventively pictured in a 1995 collage. They stand in the foreground, the Apollo in

the middle ground, and in the background three other naked male figures stand

together, the two made of bronze shown back and front, one made of stone like the

Apollo, Kleobis, and Biton figures, all more mature and classical in style than they.

It is as though we are looking at three male Graces rather than three female Graces.

The fragments of a sculpture of a male figure stand in the center of the work. It

is as though they have been recently excavated from the past, and are waiting to

be put together in a glorious whole, like the other figures. But the disconcerting

fragmentation of the figure suggests it may be a discombobulated modern sculpture.

It's springtime in the garden—the flowers, many pure white, are in full bloom, and

the foliage is radiantly green. All the figures are handsome and statuesque, majestic

and sacred, in the prime of life, their bodies perfect and healthy—whole and

wholesome, unlike the absurd "modern" sculpture. They are presided over by what

seems like a mother goddess, a few strands of luminous gold draping her naked

brown torso and one arm. In other pictures the feminine makes its presence felt in

the colorful petals that hover in the air, levitating like spirits. In still other pictures

a rather grand—enormous—female head presides over the scene. In yet others two

female figures, solid classical goddesses or ghostly Elizabethean ladies, watch over

the male figures, caring for them as Mother Nature does.

These pictures are strikingly haunting, and archeological dreams in more ways than one.

Donald Kuspit from Odyssey of Dreams: Basil Alkazzi's Spiritualism 2012