BASIL ALKAZZI-

AN ODYSSEY OF DREAMS

A Decade of Paintings 2003-2012

BY DONALD KUSPIT

Dreams express that innate mental activity which thinks, feels and receives impressions, and engages in speculation on the fringes of our everyday activities at all levels, from the most carnal to the most spiritual, without our being aware of it. By revealing the psychic undercurrents and the requirements of a life-programme written at the deepest level of our being, dreams express the individual's most cherished aspirations and, incidentally, become an infinitely valuable source of all orders of information.

Roland Cahen, Le Réve et les sociétés humaines. 1

The descent of spirit into the sphere of human consciousness is expressed in the myth of the divine nous caught in the embrace of physis .... The religions should therefore constantly recall to us the origin and original character of the spirit, lest man should forget what he is drawing into himself and with what he is filling his consciousness. He himself did not create the spirit, rather the spirit makes him creative, always spurring him on, giving him lucky ideas, staying power, "enthusiasm" and "inspiration." So much, indeed, does it permeate his whole being that he is in gravest danger of thinking that he actually created the spirit and that he "has" it. In reality, however, the primordial phenomenon of the spirit takes possession of him, and, while appearing to be the willing object of human intentions, it binds his freedom, just as the physical world does, with a thousand chains and becomes an obsessive idée-force.

Carl Gustav Jung, "The Phenomenology of the Spirit in Fairytales. " 2

The interpretation of dreams is the royal road to a knowledge of the unconscious activities of the mind.

Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams. 3

What is one to make of the range of works in Alkazzi's oeuvre? Is there any consistency in his development, any thread of concern that links them, any consciousness common to all of them—or rather anything unconscious that they have in common, that underlies the consciousness of body and nature evident in them? If, as the title of the exhibition suggests, his life is an ''odyssey of dreams,'' is he then an artistic Odysseus, wishing to return home, and dreaming all the adventurous way? Alkazzi begins the 1960s making a series of figures, all more or less abstract. Portrait and Christ Crucified, both 1960 are hardly identifiable as such, each being no more than a stem-like vertical supporting a cup-like horizontal, more or less featureless. We could be looking at a flower or goblet, or both condensed in one form, considering that condensation is one of the mechanisms at work in dreams, as Freud has shown. The isolated “figures”—presumably human bodies, however strangely unhuman their bodies—are peculiarly iridescent, as though inwardly luminous. It is as if the blackness surrounding them has infected them. Both works are morbidly barren and melancholy, although the Portrait is toned with heavenly blue, overcast so that its luminosity seems veiled, not to say repressed. Four figures, all tersely drawn as though by a child, as their eccentric simplicity suggests—Youth and Bird and Mother and Child, both 1962, Figures in Landscape, 1963, and Mother and Child IV, 1964—reverse the figure/ground and light/dark relationship. The figures are now pitch black, and nominally representational as well as abstract sketches—their bodies are clearly human, however crudely schematic—and set in the paper's empty white space, so that they dramatically stand out, as though invested with instinctive urgency. In the mid-sixties the melancholy mood remains, as Nocturnal Landscape and Pregnant Woman and Bird, both 1966, show, but in the late sixties Alkazzi begins to lighten up—almost. In Lovers in Saida and Transmutation of Lovers I and II, all 1969, the sky above the lovers is half blue and half black, the earth below them is brown, like their glowing-in-the-dark bodies. They are a little fuller than those in Figures in Landscape, but, like the other figures in the early sixties works, all but bare bone, and smaller in the vast, seemingly infinite space of the barren landscape. The Lilliputian figures seem to be anxiously engaged in a furtive sexual ritual. But with the Old House images of 1970—ending an old decade and beginning a new one—a new openness and fresh light take over the picture, and abstract form (geometrical) and realistic representation converge, suggesting a new aesthetic sophistication. Similarly, with the 1974 Desmond Series, the body becomes unequivocally human, anatomically correct, and defined in some detail. It loses its abstractness and anonymity—abstractness and anonymity go together. We are looking at an individual, not a primitive sign.

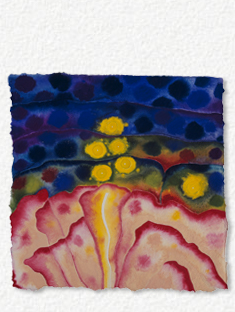

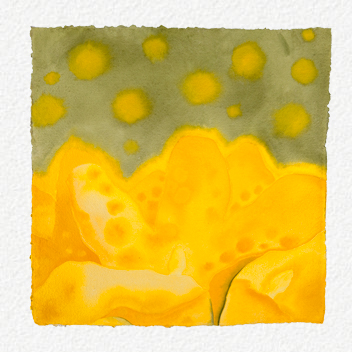

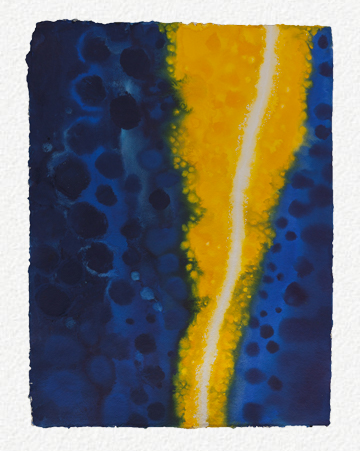

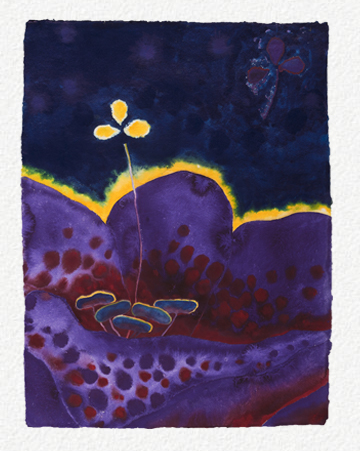

In the early eighties, beginning already with Moving Path Awaiting the Moment and the Birth Series, all 1979, what I want to call a spiritual breakthrough occurs in Alkazzi’s work. Pure forms, geomorphic and biomorphic, become emblematic of pure spirit in action—pure spirit in Kandinsky's sense of being possessed by "inner necessity" and in Jung's sense of being possessed by "divine nous." Such works as Look, See, Listen to Moments Cast Within the Seal, 1988, Ascending Angel, 1996, and Sea of Spirit Dreams, 1997, make Alkazzi's spiritual intention clear. Perhaps most startlingly, Alkazzi's persistent focus on Christ's two hands, holding the goblet of wine, and isolated in blackness—in effect what mystics call "the dark night of the soul" —in the resolutely realistic Last Supper Series, 1992, clearly conveys his belief in the sacred. This tour de force series is followed by another that includes Moments within Moment of Love Transmuted and Transmuted Beatitudes among other geometrical abstractions made between 1989 and 1991, and anticipated in earlier works of the 1980s. These works have their place in the tradition of mystical or transcendental abstraction inaugurated by Kandinsky. And yet another sequence—the gloriously picturesque collages and photomontages of 1994, realistic fantasies which in my opinion have a special significance in Alkazzi's oeuvre. And finally, in yet another consummate group of works, the pantheistic "dreams of nature" that began in 2006 and continue to the present day. All these works, however different in style and method, are spiritually confident in a way the earlier works were not.

This brief, incomplete tour of Alkazzi's works—I’ll return to some of them later—suggests his basic, recurrent themes: nature, the human body, love, and birth, all spiritual in import. The early works involve what have been called "trials of the soul on its spiritual journey" —“crises related to the person's efforts to break out of the standard ego-bounded identity, " 4 or, as Jung puts it, a journey from ego to self, a journey of self-realization—and the later works show the journey finally and successfully completed, the self spiritually at home and one with itself. Alkazzi's "odyssey of dreams" is a spiritual odyssey : his early works are spiritually suggestive, that is, involve what might be called presentiments of spirit in the body and nature, evident through the abstract transcendentalizing that compromises them, his later works show them possessed by spirit, in Jung's sense , that is, divinely inspired and enthusiastic, being enthusiastic originally meaning possessed by a god. Their numinous character suggests as much. 5 The psychoanalyst Henri Ellenberger has famously argued that all significant creativity emerges from what he called a "creative malady, " 6 suggesting that Alkazzi's later work is the creative cure for the malady that seems evident in his earlier work.

For Alkazzi the aim of art is spiritual enlightenment, an aim realized in all periods of art, from antiquity, as the ancient sculptures of humanized deities he quotes in some of his collages and photomontages show, to modernity, as his abstract renderings of nature show. Just as the ancient sculptures integrate numinous and natural experience of the human body, making it seem ideal without denying its physical reality, so Alkazzi's abstract images of nature idealistically "numinize" it without denying its physical reality. The body and nature acquire a presence they do not have in everyday experience, confirming that they are sacred and extraordinary. Initially Alkazzi's nature is desolate and sterile like a desert. Animals sometimes appear in the desert, seen from a distance as though to confirm its vastness. Later, nature becomes fertile with colors and flowers, like the South of France, where Alkazzi now lives. One might say he's gone from one extreme to another-emotional as well as physical extreme, for the later works seem more intimate than remote. Similarly, Alkazzi's later bodies are bigger, more full-bodied and muscular than the earlier bodies, which are sort of token bodies, signs of the body with no visceral presence, self-evidently so in Lovers, 1963. Finally love, which seems like an impersonal, desperate physical act in the early works, becomes personal and, one might say, spiritually relaxed, intimate, and caring in the later works.

But life begins with birth, and Alkazzi depicts the moment of birth with exquisite delicacy in a number of abstract fantasies. The infant emerges from the darkness of the womb into the light of day, although sometimes it is stillborn and the light is moonlight, as in Life and Birth of a Dead Foetus, 1966. In this work, along with Pregnant Woman and Bird and Mysteries of Nocturnal Landscape, luminous lines and amorphous shapes—forms that seem in metamorphic process—are isolated in black space, as though in an abyss. The embryonic forms, still incompletely differentiated, hang between life and death, suggesting that the outcome of birth— whether of art or life—is uncertain. These works are surreally intimate, ingeniously evocative of the trauma of birth, for many psychoanalysts the model for all traumas, for it involves expulsion from the paradise of the mother's womb, and with that literal separation from her body. Birth is thus a catastrophic break in the continuity of being, as the psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott wrote, and with that, paradoxically and unexpectedly, an experience of death. One unconsciously feels that one is dying at the moment one is being born. Thus the eternal darkness of death surrounds the small light of growing life in Alkazzi's birth pictures. The small moment of "enlightenment" in the nocturnal landscape has Gnostic import; one must "see the light" in the darkness to save one's soul. One can regard Alkazzi's odyssey of dreams as a journey from darkness to light—from a nocturnal landscape, in which nature is empty and deserted, the figures a small oasis of light in it, to a sunlit landscape, in which nature is flourishing and full of light, ensuring that everything—organic or inorganic, human or not human (animal, vegetable, or mineral)—has a soul as well as a body. Nature is mothering—empathic and energetic—in the sunlit landscapes; in the nocturnal landscapes she is apathetic.

No longer a part of one's mother's body, one begins to realize one has a body of one's own—pathetically small and helpless, as in the 1978 Birth Series. Similar small bodies, now engaged in sexual activity, appear in Alkazzi's early lovers works, suggesting that love is unconsciously regressive, for it involves the intermingling of bodies, thus unconsciously recalling the intermingling of mother and infant bodies during pregnancy. Indeed, making love is a "pregnant" moment—symbolically pregnant with unconscious meaning, to use Ernst Cassirer's phrase—and can lead to pregnancy. Freud regarded the oceanic experience of mystics as a symbolic return to the mother's womb, reminding us that life began in the ocean, and birth is signaled by the breaking of the mother's water—that without water there is no life. perhaps suggesting the unconscious reason that Alkazzi lives near the Mediterranean Sea, its waves reflected in his ecstatic nature imagery of the last decade. With subtle bizarreness Alkazzi captures the moment of birth, when we are vulnerable and anxious but also strangely innocent, for we do not know what is happening to us. I think it requires a certain mystical genius to make these works, if mysticism involves "obscure self-perception," as Freud suggested. 7 Mysticism involves great capacity for inwardness, the sustained ability to stay in touch with one's unconscious, and by way of that, with the collective unconscious, and imaginatively and consciously externalize the unconscious in and through art, and thus numinously communicate it to others, putting them in touch with their unconscious, making them aware that they have a certain capacity for inwardness. Theorists as different as Anton Ehrenzweig and Edward 0. Wilson argue that convincing art has an emotional impact on us before we understand it, and even if we never do, and Alkazzi's images make an emotional impact on us whatever their cognitive meaning.

I've mentioned that I think Alkazzi's collages and photomontages have special significance in his oeuvre. They're consummately beautiful; different elements harmonize in a garden of paradise, sometimes mountainous, sometimes a hortus conclusus, always serenely vital. For all the activity and crowds of people in At the Beach, a memory of Alkazzi's visit to Japan, the figures are happily together, whether seen up close at the banquet table in the foreground or in the crowd in the distant background. Wherever they are, they are all very particular individuals, all young, all enjoying life. Even when, as in The Rape, the picture fragments into physically incompatible parts, reminding us that "there is no excellent beauty that hath not some strangeness in the proportions," as Francis Bacon wrote, 8 it remains self-consistent emotionally. The parts are all actors in the same violent drama. But what makes The Rape, and all the other collages and photomontages particularly interesting, is their quotation—postmodernists would say appropriation—of historically important works of art. Some are modern, like Manet's Oejeuner sur l'herbe, 1863, which alludes to Giorgione's traditional Pastoral Symphony, ca. 1508, and is the centerpiece of The Rape. Two of the heads, one of a naked female, the other of a clothed male, from the Manet make a brief appearance in Landscape of Dreams V, another collage.

Other appropriations are ancient, like the archaic sculptures of Apollo and of Kleobis and Biton, two standing male youths (kouroi), in a garden of paradise, inventively pictured in a 1995 collage. They stand in the foreground, the Apollo in the middle ground, and in the background three other naked male figures stand together, the two made of bronze shown back and front, one made of stone like the Apollo, Kleobis, and Biton figures, all more mature and classical in style than they. It is as though we are looking at three male Graces rather than three female Graces. The fragments of a sculpture of a male figure stand in the center of the work. It is as though they have been recently excavated from the past, and are waiting to be put together in a glorious whole, like the other figures. But the disconcerting fragmentation of the figure suggests it may be a discombobulated modern sculpture. It's springtime in the garden—the flowers, many pure white, are in full bloom, and the foliage is radiantly green. All the figures are handsome and statuesque, majestic and sacred, in the prime of life, their bodies perfect and healthy—whole and wholesome, unlike the absurd "modern" sculpture. They are presided over by what seems like a mother goddess, a few strands of luminous gold draping her naked brown torso and one arm. In other pictures the feminine makes its presence felt in the colorful petals that hover in the air, levitating like spirits. In still other pictures a rather grand—enormous—female head presides over the scene. In yet others two female figures, solid classical goddesses or ghostly Elizabethean ladies, watch over the male figures, caring for them as Mother Nature does.

These pictures are strikingly haunting, and archeological dreams in more ways than one. Like all dreams they are wish-fulfillments, and the wishes they fulfill are sexual and narcissistic. The archaic Apollo is Alkazzi's self-symbol, and the kouroi standing together are male lovers, like the earth-colored figures in Seascape with Figures I and II, Angel and Lover III, both 1980, and Transmuted Lovers, 1984. In the last image they are inseparably intertwined, even more totally connected than the figures in Mother and Child IV. There is a similar intimacy, involving narcissistic mirroring, as true love always does (if only in fantasy form), in Metamorphosis—Spirit Artist—Reflections and Dreams, 1995, which alludes to Pliny's account of the origin of painting, which involved "tracing the shadow of a man with lines. " 9 Alkazzi's manly lovers are in effect shadows of each other, however different the manner of representation of the 1980 and 1995 lovers.

I suggest that these representational works, along with such abstract works as Interpenetrating Triangles/Ezra, 1994—one among many similar works showing intersecting triangles, made at the same time or earlier—involve what Ellenberger calls "sexual mysticism." 10 In some works the triangles are surrounded by a halo of stars, making the mystical point clear. Sometimes bands or lines of white light intersect to form a triangle. The triangles are all equilateral: "Equilateral triangles symbolize the godhead, harmony and proportion . Since all procreation proceeds from division, humans correspond to an equilateral divided into two, that is, with a right-angled triangle. " 11 It is a strangely narcissistic moment, subliminally sexual, like the moment pictured in Metamorphosis—Spirit Artist—Reflections and Dreams. In a sense, Alkazzi's later works recapitulate the moment of birth depicted in his earlier works, with the difference that self-love and self-reflection are enough to make one creative. Broadly speaking, he is concerned with the rare moments in which narcissistic and sexual mirroring become one gloriously divine moment, a moment of self-realization in which one feels and becomes God-like. God has the power to originate—what Jung calls "primordial spirit" and what Winnicott calls "primary creativity." One might say that Alkazzi's art is a meditation on the primary creativity of the primordial spirit called God, sometimes materialized in human form, at other time immaterially abstract, a sort of self-referential sign of itself, but always self-contained, and always seemingly parthenogenetically pregnant with life, as nature seems to be. The pure godhead, inherently creative, is the dream home which his art finally reaches.

Bring two pure right-angled triangles "sexually" together to form an equilateral triangle and you have a mystical house of God. Indeed, sometimes Alkazzi's triangle is a temple—Alkazzi’s earlier imperfect house transformed or, to use his word, transmuted into the perfection of a temple, much the way his lovers are transmuted into angels, that is, spiritual beings, and with that fully self-realized. Love becomes unequivocally spiritual in Alkazzi's later works, suggesting—as I want to do—that his works are religious icons, a point made explicitly clear by his Angel, Three Angels, and Five Angels, all 1999, and above all by the The Last Supper Series, stripping away all those who were present at it so that we alone can witness it, zeroing in on the hands that hold the goblet from which He drinks the wine that He miraculously transforms into His blood, and which bless us despite the fact that we have betrayed and denied Him, as Judas and Peter did. The medieval religious icons that Alkazzi quotes in a 1995 collage—they tell the story of Christ—make my point about his works being religious icons clear. A religious icon painting is a "sacred and venerated object…vested in the transformative and transcendent experiences of envelopment and ekstasis. " 12 At its most consummate, sexual experience can be ecstatically enveloping, making it transformative and transcendent, that is, it seems to afford the same "access to another spatial and temporal dimension" that a religious icon painting does. This is what it means to be "transformed by love”— true love of another human being and especially of God—and to feel that one has "transcended" everyday space and time, experienced a "timeless and out of this world moment," confirming that one's body has "spirit." Sexual experience can be spiritually nourishing however physically depleting. It can be sacred, however seemingly profane. In Alkazzi's early nocturnal desert works it seems profane, in the later nature works it seems sacred. But in both works it is creative.

The lines in the upper part of the 1993 Metamorphosis Series intersect like the wings of an angel, and the triangle beneath them is in effect its body, or rather its disembodied pure spirit. Angels are pure spirits—invisible until the flash in the sky, as it were, like the "comets" in the Eternal Whisperings Series, 1999, metamorphosizing into the ecstatically luminous organic forms in The Rites of Spring and similar "Spring Dreams" pictures, as I want to call them, that begin to appear from 1999 onward. They finally transform into the glorious flowers that begin to appear in 2006, heralded by the magnificent lily that appears in one of the collages. Like Mondrian's flower paintings they are sacred icons, but unlike Mondrian's flowers those of Alkazzi are not decaying and melancholy but jubilant and growing—not nature on its last legs, ready to be abandoned in Mondrian's geometrical abstractions, but nature full of joie de vivre, all the more so because it remains mystically abstract. Alkazzi's flowers are angels in another form, reminding us that angels are supernatural, immaterial beings able to give themselves natural, material bodies, thus miraculously revealing their presence. Alkazzi's works are revelations, and also make it clear that sex can be a spiritual revelation, as the Annunciation ingeniously suggests. The Angel Gabriel tells Mary—spiritually pure because she is a virgin and will remain one forever—that she will be impregnated by God ( vicariously through the manly Gabriel?) and give birth to his Son, mysteriously becoming a mother, that is, creative, informed by the Holy Spirit, housing it in her body. The Annunciation suggests that all sexual acts are implicitly—potentially—spiritual, and all spiritual acts, including making art (certainly religious icons), are implicitly sexual.

A final comment, by way of Freud, about Alkazzi's portraits of Jack Woolley, Tim Powell, Carlo Piazza, Ronald Kuchta, Patti Palladin, and Eva J. Pape, among other people. All are convincing "speaking likenesses," but more to the point is that they are "dream portraits," in Freud's sense of the dream. "Dream-imagination,' Freud wrote, "is susceptible in the subtlest manner to the shades of tender feelings and to passionate emotions, and promptly incorporates our inner life into external plastic pictures. " 13 Alkazzi's portraits of friends are full of tender feeling and passionate emotions, suggesting his devotion to them, and suggesting the subtlety of his" artistic work," which is what Freud called "dream work.”

Notes:

1. Quoted in Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrant, The Penguin Dictionary of Symbols (London: Penguin, 1996), 311.

2. Carl Gustav Jung, "The Phenomenology of the Spirit in Fairytales," The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, Collecte Works (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1959) , II, 212-13 .

3.Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams, Standard Edition (London: Hogarth Press and the Institute of PsychoAnalysis,1953), IV, 647.

4. David Lukoff, "Visionary Spiritual Experiences," Psychosis and Spirituality: Consolidating the New Paradigm, ed. Isabel Clarke (London: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), 207.

5. For Rudolf Otto, numinous experience involves the feeling of "pious or religious dependence," and with that a sense of being in the presence of something tremendous and mysterious (the "mysterium tremendum") (Otto, The Idea of the Holy [New York: Oxford University Press, 1958], cited in J. J. Pollitt, ed., The Art of Greece 1400-31 B.C. [Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1965], 34. For many romantics-such as Alkazzi-nature is inherently numinous, arousing feelings of overpowering awe involving the sense of being overpowered-and simultaneously empowered-by its energy, and submerged in or merged with its otherness. For Otto the numinous is a "unique ... category of value" recognized when one is in a "'numinous' state of mind,"suggesting that the capacity for numinous experience is innate to human nature (cited in Henri Ellenberger, The Discovery of the Unconscious: The History and Evolution of Dynamic Psychiatry [New York: Basic Books, 1979], 534). The numinous can also be felt in the human body, as the ancient sculptures, both archaic and classical, of the naked male body and the draped female body-gods and goddesses- that Alkazzi features in some of his collages make clear.

6. Henri Ellenberger, "The Concept of Maladie Créatrice," Beyond the Unconscious: Essays in the History of Psychiatry (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), 328-40.

7. Quoted in Ellenberger, The Discovery of the Unconscious, 534

8. Quoted in E. F. Carritt, ed., Philosophies of Beauty from Socrates to Robert Bridges: being the sources of aesthetic theory (New York and London: Oxford University Press, 1947), 56.

9. Quoted in J. J. Pollitt, ed., The Art of Greece 1400-31 B.C. (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1965 ), 34.

10. Ellenberger (The Discovery of the Unconscious, 545) notes that "sexual mysticism" has a long history, traceable from Plato to Schopenhauer. It is inherent to romantic philosophizing about nature and cabalistic thinking. It is sometimes called "sexua transcendentalism," sometimes the "metaphysics of sex." It involves the assumption of "the fundamental bisexualit of humans." It is alchemically represented by a hermaphrodite, often standing in triumph over a dragon and worldly globe symbolizing chaos. The dragon symbolizes the threatening instincts, the worldly globe the chaos that results when they are allowed to run wild, overwhelming consciousness. But the circular globe contains a triangle, that is, the seal of the godhead, a sign of spiritual consciousness. The hermaphrodite symbolizes "the alchemical goal of coniunctio. the union of opposites (male and female, consciousness and the unconscious, etc.)" the dialectical ambition of the creative spirit. A famous illustration of "the philosophical egg" that is the "birthplace" and "container" of the creative spirit appears in Marie-Louise van Franz, Alchemy: An Introduction to the Symbolism and the Psychology (Toronto: Inner City Books. 1980) cited in Ellenberger, The Discovery of the Unconscious, 534. As Kandinsky wrote, "art in many respects resembles religion," for both belong to "the spiritual life," which "consists in moments of sudden illumination. resembling a flash of lightning," which helps us understand Alkazzi's alchemical art, all the more alchemically creative when it is abstract (eds. Kenneth C. Lindsay and Peter Vergo, Kandinsky: Complete Writings on Art [New York: Da Capo Press. 19941, 377, 131).

11. Chevalier and Gheerbrant, 1034.

12. Stephen James Newton, Painting, Psychoanalysis, and Spirituality (Cambridge, UK ..ind New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 167.

13. Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams, Standard Edition (London: Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho- Analysis;1953), lll, 118.

© 2013 Scala Arts Publishers,Inc

All rights reserved. This may not be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher.

© Basil Alkazzi, All Paintings

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American copyright conventions.